“TUI” in R - Rendering and key presses

To preface, I don’t think R is a language designed to be run end to end in the terminal. R’s ‘killer app’ is making plots, and the terminal isn’t really designed to display these. Therefore sitting in a REPL and just rerunning the same commands or scripts (but maybe slightly tweaking them) is a much more natural programming experience. The most common way to abstract this sort of R code for end-users is to create a Shiny app, but for fun lets try making a terminal UI (TUI) in R.

This is not aiming to be anything more than an interesting blog post.

The “TUI” I create focuses heavily on the system() command, and is more akin to writing a simple TUI in bash than something fully fledged like vim or emacs.

If you wanted to properly make a TUI in R then the de-facto library is ncurses (which has a R wrapper).

This blog is more of a fun exploration into how R interacts in Rscript vs the REPL, as well as an exploration into ASCII, keypresses and why cat('\014') clears your console.

The Basics⌗

For reference: I’m using MacOS. I’d guess 90% or so of this probably won’t work on Windows but should work on any other *nix platform (or in WSL).

system() is an R function which lets you submit a string to your shell to be executed.

For example, in any R session (including an RStudio session) you can do

system("echo Hello, world!")

# Hello, world!

system("echo Hello, World!", intern=TRUE)

# [1] "Hello, World!"

Pretty printing⌗

Just printing plain ol' text would make this really boring.

We can spice things up with the already existing cli package.

This adds a dependency BUT removes the need to write loads of functions that print things in a nice way, which seems like a fair trade.

cli adds simple header functions, such as cli_h1() and cli_h2(), as well as nicely formatted errors via cli_abort().

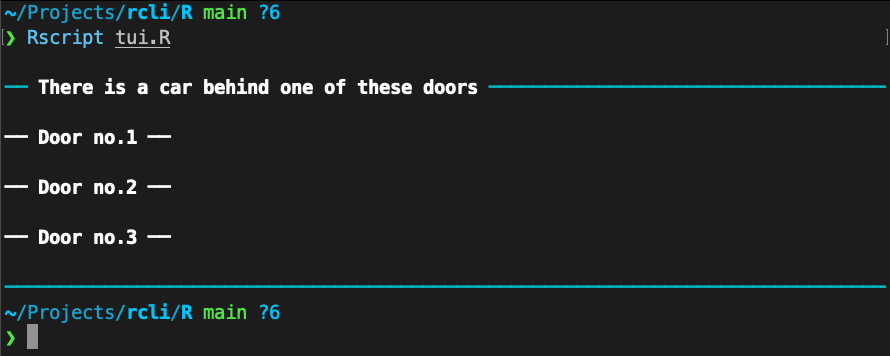

We can now print a simple ‘UI’.

library(cli)

cli_h1("There is a car behind one of these doors")

cli_h2("Door no.1")

cli_h2("Door no.2")

cli_h2("Door no.3")

cli_h1("")

When we run this in the terminal, we need to first clear the screen.

Some of you may know of cat('\014') to clear the console in RStudio.

This however will not clear the whole terminal in an Rscript session.

I won’t get into exactly why this happens yet, but hopefully it will be explained by the end of the post.

To clear the terminal we have two options:

- Send ANSI escape codes to the terminal via the

catcommand with the proper escape character (e.g.cat("\x1bc")) to clear the terminal - Use the

tputterminal command within asystemcommand

I found the tput commands to be easier to work with, so I will use these throughout.

We can now clear the screen using tput clear.

system("tput clear")

cli_h1("There is a car behind one of these doors")

...

As we will be using this a lot. Let’s put this into a function

draw_screen <- function() {

system("tput clear")

cli_h1("There is a car behind one of these doors")

for (i in 1:3) {

cli_h2(c("Door no.",i))

}

cli_h1("")

}

A main loop⌗

R doesn’t have a ‘main’ entrypoint like in python or C, but we can easily define one to help organise our code. Inside the function will house the loop that will be used to process input, render the display, and manage any other component we expect to change. Anything outside of the loop can be thought of as a sort of initialiser for the TUI.

main <- function() {

repeat {

draw_screen()

}

}

main() # Our 'entrypoint'

If we now run our script, you will be greeted by an infinitely rendering loop which will clog up your terminal, you’re welcome (also you’ll need to exit by doing CTRL-C).

This is because tput clear simply prints a bunch of empty lines into your terminal, to push what is currently on the screen upwards.

To stop this, inside our draw_screen function we can change tput clear to tput reset, which instead reinitalises a whole terminal and doesn’t spam a bunch of empty lines.

function draw_screen() {

system("tput reset")

...

}

main <- function() {

system("tput clear")

repeat {

draw_screen()

}

}

We still keep the tput clear initially, so what was previously run in our terminal is available if you scroll up.

Basics of reading input⌗

R has some built in functions to help read lines. However these are all unsuitable.

readlinedoesn’t work in RScript, so that’s immediately out of the question.readLineshas some limitations, most notably that it requires you to press enter/return to submit a line, this is fine for when we want to receive input like a name, but not so good for receiving input like an arrow key.

The simplest method is to actually use our trusty friend system again.

We can use the read command to get input.

read has the option -n, which allows you to specify how many characters you wish to receive before returning - in our case we only want 1.

I struggled to get read to print the output it received, but it’s okay because we can store this in a variable and just echo it back.

draw_screen <- function() {...}

read_char <- function() {

system("read -n 1 tmp; echo $tmp", intern = TRUE)

}

main <- function() {...}

For those wondering, the $tmp variable will not persist after the RScript is done.

We can now get some input to our program.

main <- function() {

system("tput clear")

repeat {

draw_screen()

x <- read_char()

}

}

Now you may notice that as you press any key the character or code will flicker for just a second, this is because there’s a slight delay before draw_screen() is called.

Disabling echo⌗

It’s time to introduce something else, the stty command.

This command focuses entirely on the settings of your current terminal.

These setting are how the terminal knows not to echo back when you’re typing a password.

If you type stty -a into your terminal you’ll get back a bunch of funky information about what ‘flags’ are currently enabled in your terminal.

Before we start messing with this, we want to save our current settings.

We do this with stty -g, which returns a string of all our options that can be provided back to stty at a later point.

main <- function() {

current_settings <- system("stty -g", intern = TRUE)

system("tput clear")

...

}

To be more defensive, if we can’t get the output from stty -g we abort the program so we don’t start randomly changing flags and breaking the terminal.

When a command fails whilst using system we get returned back an object with a status attribute.

The value of status doesn’t really matter - we can assume that any non-null value of status is a bad thing, and we should probably stop.

main <- function() {

stty_orig <- system("stty -g", intern = TRUE)

if (!is.null(attr(stty_orig, "status"))) {

cli_abort("STTY COULD NOT SAVE")

}

system("tput clear")

...

}

Now, we want to change our loop slightly.

We want to ensure that if the loop fails at any point.

We recover the original terminal settings before terminating.

R has tryCatch(), which has the finally parameter.

The expression given to this parameter is executed once the code in tryCatch is ‘complete’ (that includes whether the code failed or not).

main <- function() {

stty_orig <- system("stty -g", intern = TRUE)

if (!is.null(attr(stty_orig, "status"))) {

cli_abort("STTY COULD NOT SAVE")

}

system("tput clear")

tryCatch({

repeat {

draw_screen()

x <- read_char()

}

},

finally = system(glue::glue("stty {stty_orig}"))

}

The cli package already depends on the glue package so we can use the glue::glue function instead of a paste to write the string without including another dependency.

Now, we can finally disable the ‘echo’-ing of character.

We do so with stty -echo -icanon.

Echo disables the echo-ing of characters, icanon changes how the input is processed.

See here for more info (search for ‘Canonical and noncanonical mode’).

We can now formally print back our input received from read_char().

main <- function() {

stty_orig <- system("stty -g", intern = TRUE)

if (!is.null(attr(stty_orig, "status"))) {

cli_abort("STTY COULD NOT SAVE")

}

system("tput clear")

system("stty -echo -icanon")

x <- ""

tryCatch({

repeat {

draw_screen()

print(x)

x <- read_char()

}

},

finally = system(glue::glue("stty {stty_orig}"))

}

What are key presses?⌗

If you already know about ANSI escape codes, then skip ahead to the next section

With our above code, we can now see the result of our key presses and do a bit of exploring. When we press a character, number or punctuation key, we are returned back the same punctuation or character. A key like backspace or escape returns a unique code. Now press an arrow key. This actually sends multiple different characters, you may notice your console flickering. We can have a closer look at how these key presses work by slightly modifying our code.

main <- function() {

stty_orig <- system("stty -g", intern = TRUE)

if (!is.null(attr(stty_orig, "status"))) {

cli_abort("STTY COULD NOT SAVE")

}

system("tput clear")

system("stty -echo -icanon")

x <- ""

tryCatch({

repeat {

draw_screen()

print(x)

x <- c(read_char(), read_char(), read_char)

}

},

finally = system(glue::glue("stty {stty_orig}"))

}

Now when we run and press the up arrow key, you should see

[1] "\033" "[" "A"

This is actually a case of the aforementioned ANSI escape code.

The first 32 characters of the ASCII are reserved as ‘control characters’.

These are your newlines, TAB keys, etc…

One of these is specified as the “Escape sequence”.

This is number 27, which is 033 in Octal and 1b in Hexadecimal.

This is why you see "\033" returned in the vector.

Online you might also see this escape sequence referenced online as \x1b or 0x1b for the same reason.

It all means escape sequence.

The [ means that we can expect parameters after this, in this case, we are just giving the singular 'A'.

Within the ANSI Control Sequences we can see that this corresponds to the ‘Cursor up’ command.

Hold on a minute! ‘\033’ looks familiar

If you’ve ever typed cat("\014") you’ve used ASCII control characters already!

The ‘form feed’ control has already been mentioned in this post.

It prints empty lines to push what is currently on the screen upwards.

Looking in the control code chart you can see that ‘form feed’ corresponds to 014 in octal, 12 in decimal and 0C in hex.

Therefore instead of cat("\014") you can type cat("\x0c") to achieve the same result.

How to handle arrow keys⌗

So in order to correctly handle keypresses, we need to first check if we recieve a keypress of '\033'.

If so then we need to get the two more characters back: firstly the '[' and then our actual code value.

read_char <- function() {...}

read_keypress <- function() {

char1 <- read_char()

if (char1 == "\033") {

square_bracket <- read_char()

code <- read_char()

switch(code,

A="UP_KEY",

B="DOWN_KEY",

D="LEFT_KEY",

C="RIGHT_KEY",

default = code)

} else {

char1

}

}

main <- function() {...}

If we rerun our tui.R, we should get back a single string of "UP_KEY" back instead of the 3 individual characters.

Now we can program moving up and down in the terminal.

To do this we will have to refactor both main() and draw_screen().

Our main() function will now have a persistent cursor variable, which it will pass to our draw_sreen().

main <- function() {

...

tryCatch({

cursor <- 0

repeat {

draw_screen(cursor)

x <- read_keypress()

if (x == "UP_KEY") {

cursor <- (cursor - 1) %% 3

} else if (x == "DOWN_KEY") {

cursor <- (cursor + 1) %% 3

}

}

},

...

}

To make it clear which option we have selected, we can use the bg_green() function from the cli package alongside an if statement.

This will set the background of the currently selected option green.

draw_screen <- function(cursor) {

system("tput reset")

cli_h1("There is a car behind one of these doors")

for (i in 1:3) {

if (i-1 == cursor)

cli_h2(bg_green(c("Door no.", i)))

else

cli_h2(c("Door no.",i))

}

cli_h1("")

}

read_char <- function() {...}

When we run tui.R we are able to move up and down between options.

However we still can’t quit.

Thankfully, we’ve already done 90% of the work!

when we press CTRL+Q, a similar escape code of "\033" "[" "\021" is sent to the terminal.

Hence we can simply account for it in the if ... else in main().

main <- function() {

...

tryCatch({

cursor <- 0

repeat {

draw_screen(cursor)

x <- read_keypress()

if (x == "UP_KEY") {

cursor <- (cursor - 1) %% 3

} else if (x == "DOWN_KEY") {

cursor <- (cursor + 1) %% 3

} else if (x == "\021") {

break

}

}

},

...

}

Which simply breaks out of our loop and ends the tryCatch().

Final thoughts⌗

I hope this blog helped formalise a few parts of programming in R that we take for granted, such as cat("\014").

I will be presenting a full talk on writing shell scripts in R at the PHUSE US connect 2023, in my talk “A journey through time and resourcing - a use case for R shell scripts” in the “Open Source Technologies” stream. Please feel free to message via LinkedIn if you have any questions or wish to know more.